For a long time I have championed immigrants. I personally understand the rage and frustration behind unfair immigration policies, policies that wouldn’t let my husband’s family members get a visa to come to the US for ten days in order to watch his marriage. I also had enough white privilege that my parents could make a contribution to a certain senator’s campaign fund to get that decision reversed so my family members could come visit me.

When I saw the news of children being separated from their parents at the border it hit me like nothing else. I immediately signed up to make a monthly contribution with an organization that worked to bring parents and children back together. I still feel rage and impotence every time I think of children being separated from their already-brutalized, already-war-weary parents. I’ve seen how people in Central America live. I’ve visited a neighborhood in Honduras that was built over a trash heap, watched children scamper around that filth, watch their parents with looks of resigned desperation.

I know those parents would do anything to give their kids a better life.

But here’s what I also know.

For a long time, I’ve watched cases of police brutality against black Americans, and I’ve felt some frustration. Some. Frustration. Not a lot, mind you, but a little. Enough to debate the issue with loved ones but not enough to call my senators and demand change.

I haven’t really thought about racial inequality in this country, have only been vaguely bothered by statistics of black men being incarcerated at six times the rate of white men. Six times! (But that’s an improvement–it used to be seven times in the early naughts).

This is all just a little ironic because it’s not as if I grew up divorced from black communities. I grew up, lived, went to school, right smack dab in the middle of a hugely racially diverse community. My school was 65% black, 45% white.

But here’s the thing.

Even though I had a couple of black friends, I didn’t have any real, emotional in to the black community. I didn’t visit black churches, go to black homes, sit down and eat lunch with black neighbors very often. That’s all on me.

I grew up in a racist town in the deep South, dear readers. No other word for it. The systemic, racist duality that existed and still exists in my hometown would blow your mind. It’s still blowing mine, as I deconstruct my experiences.

And yet. I’ve never let myself be overly bothered by the inequalities and injustice my neighbors live out every day and that are happening in my own back yard. And I’m a part of it. I grew up in these racist structures and I still contribute to systematic inequality in this country.

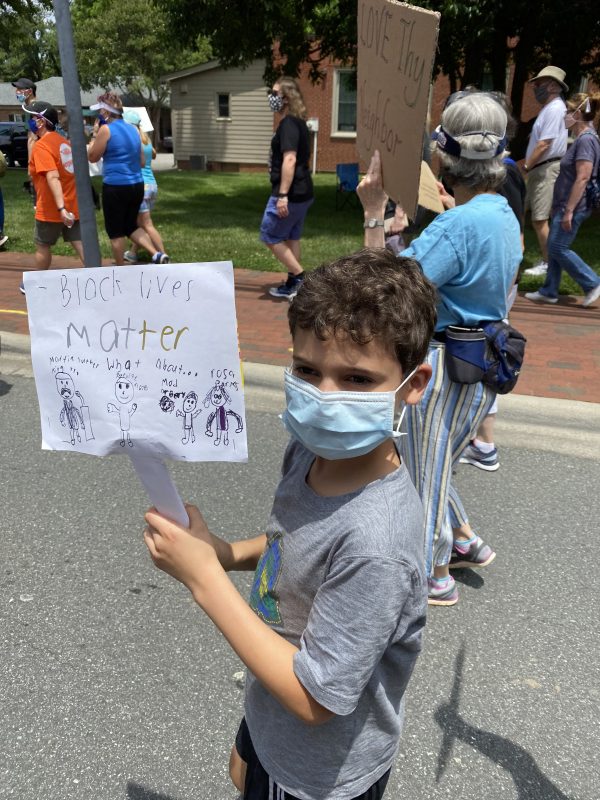

So, all of a sudden, with three bone-jarring black deaths in a row, with Americans filling the streets in protest, I had no other choice but to finally wake up to a reality my black friends and neighbors had experienced since birth. I started filling my social media feed with black teachers. I started buying books on racism by black authors.

I had to start paying attention, to start thinking about black parents who would do anything to give their children a better life.

And, you know what I’ve sort of suspected for a long time? Money is one the key ways that black Americans have been locked out of more positions of power and influence in this country.

The one data point you should remember from this post is that the average net worth of a white family in this country is $171,000, and the average net worth of a black family is $17,150 (Brookings).

From Brookings:

“Gaps in wealth between Black and white households reveal the effects of accumulated inequality and discrimination, as well as differences in power and opportunity that can be traced back to this nation’s inception. The Black-white wealth gap reflects a society that has not and does not afford equality of opportunity to all its citizens.”

The Brookings Institution

How can it be that two ethnic groups, both of which have lived on this continent basically the same amount of time (from the beginnings of our first colonies, back in 1619), have such wealth disparities?

Well, for one thing, blacks could not own property until 1865. That is over two hundred years of history, in case you’re counting.

It was illegal for blacks to learn how to read until 1865. Illegal.

Education, a critical component of freedom to a group of people denied it for so many years, was consistently underfunded for black Americans for decades.

After the Reconstruction, and the implementation of the heinous Jim Crow laws in the South, there were over 4,400 lynchings of people of color. A lynching, Junior ThreeYear told me, over dinner as we discussed it, is when someone takes the law into his own hands.

NO.

And who the hell taught him that?

A lynching is using deliberate, extreme violence to subjugate and control a group of people, and with said violence dehumanize them for the majority, to make them less than human in people’s minds.

Lynchers sent postcards advertising the events.

They hung black body parts in shop windows.

How can we, a nation designed upon the fundamental “all men are created equal” resign ourselves to men hanging from trees? We can’t. In the words of the brilliant Nikole Hannah-Jones, author behind the NYTimes’s 1619 Project:

The shameful paradox of continuing chattel slavery in a nation founded on individual freedom, scholars today assert, led to a hardening of the racial caste system. This ideology, reinforced not just by laws but by racist science and literature, maintained that black people were subhuman, a belief that allowed white Americans to live with their betrayal.

Nikole Hannah-Jones

And so, for centuries, black Americans have not only bared the brunt of racist policies, they have lived in a nation that thinks of them as less than. Rap music is violent. Loud, exuberant behavior is thug-like. Soul food is poor people’s food.

Black Americans today have to pay higher rates for the same home mortgage. They are discouraged from living in white neighborhoods. People see black people walking around and call the cops.

African Americans have been much harder hit by Covid-19, in part because they are more prone to heart disease and stroke.

That’s what a lifetime of being treated like a second-class citizen will do to you. It will wear down your health.

So why does this matter, and what do we do?

It matters because our country’s broken. And I don’t want my children or my grandchildren to live in that world. I don’t want anyone’s children or grandchildren to have to live in such a world.

It matters because I was apathetic for so long. And I feel so sad about that. I was wrong. But, I hold the words of Maya Angelou close,

“Do the best you can until you know better. Then when you know better, do better.”

Maya Angelou

It matters because I’m a teacher of culture. And I have to teach my students that we don’t live in “normal.” We live in a constructed, specific, culture created by white Anglo-Saxon Protestants. A culture that values time, efficiency, and individuality (kids leave the house at 18!).

But there are other cultures that do things in different ways. And they are beautiful. The Latino culture has a much different concept of “time” than the dominant white culture in the US. Relationships are prioritized, and your contributions to the family are much more important than individual accomplishments. In African-American culture, individuals are expected to make something of themselves, in order to create a positive reflection of the group, and then to share those gains with the group.

No one culture is right or wrong. They are different, and each culture has beautiful things to offer the world. We don’t have to be scared by different. We can learn about different and expand our worlds.

One of the most enlightening classes I took in my master’s program was my class on culture. I learned so much. And I need to share that with the next generation of learners as I continue to learn about cultural differences.

What else can we do, both as a community of people interested in personal finance, and as concerned citizens?

I am donating money, reading books, learning, re-working my curriculum, working with a team to hire more diverse teachers at my school, talking to Mr. ThreeYear and my kids about everything I’m reading and learning, discussing race and injustice, and following POC in the personal finance and other spheres.

I’m trying to open my world up, to my children and myself. To support minority-owned businesses, to cultivate friendships with people of color, to un-white my life a little bit.

Also, I’m thinking about people in my hometown community, and ways to improve economic inequalities for them. I don’t have good answers, but I have been thinking a lot about better short-term loans available to people who need them than payday loans, which are all over the place in my hometown but charge such exorbitant interest rates that I’m not sure they help more than they hurt.

This is a personal blog, a blog about my life, so of course it’s all about me, a white woman with heaps of privilege. But one thing I’m working on is listening to people who have been living out these injustices for years.

So I’d love more ideas for bloggers to follow, podcasters to listen to, books to read.

If you have suggestions, please include them in the comments.

If you don’t follow her already, I would highly recommend checking out Michelle Singletary. She is a personal finance writer for the Washington Post and writes a column called “The Color of Money”. I have followed her for many years and she is the real deal.

Great suggestion! I love her posts. Thanks Chris!

I love this piece. I feel the same way and after a lifetime of being vaguely aware of the problems, enough to talk a little, but not doing anything to change things, I am trying to do many of the same things. As I learn more and know better, I can do better.

I just watched this video on Upworthy.

https://www.upworthy.com/woman-puts-protests-into-historical-context

It was so powerful that it has brought me to tears. We must do better. I must do better. I am determined to do better. And I am so grateful that you are using your platform to do better, too.